This year marks the 10th anniversary of The Met’s reimagined Islamic Wing, which houses one of the finest and most comprehensive holdings of its kind. A founding series of acquisitions in the late 19th century has since flourished into a collection of more than 12,000 treasures, forged through the centuries and across the Islamic world. In 2011, the Museum unveiled 15 renovated exhibition spaces cohesively exhibited as Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. The new geographic orientation of these galleries illuminates the diversity and interconnectedness of this vast region.

In celebration of the anniversary, The Met Store is delighted to introduce the Heirloom Project. The initiative, presented in partnership with the esteemed New York City–based designer Madeline Weinrib, commemorates The Met’s exceptional Islamic art collection and assists in the preservation of traditional craftsmanship by engaging with global artisans.

Here, Islamic Art curator Navina Haidar speaks about how the New Islamic Galleries Project has conjured a more comprehensive view of the department's spectacular holdings, and discusses the magnificent late 17th-century Indian floorspread fragment that inspired our new Blooming Poppies line of bone china dinnerware, designed for the Heirloom Project by Madeline Weinrib in partnership with the Indian luxury label Good Earth.

Navina Haidar, Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah Curator-in-Charge, Department of Islamic Art pictured in The Met's Gallery for the Art of Mughal South Asia (16th–19th Centuries) (Gallery 463)

Can you tell us a little bit about your role at The Met?

I am currently the Nasser Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah Curator-in-Charge of Islamic Art. I have been a curator at The Met for over 15 years, and was appointed to this position last year.

As the coordinating curator of the New Islamic Galleries Project, what was your vision for the redesign?

The galleries were first reopened in 2011 and were envisaged as an airy and elegant space for the collections of the Islamic Art department, which are arranged by region and chronology. The quadrilateral floor plan allows for views and connections between gallery spaces, underscoring the idea that Islam connected cultures to develop a related visual language. While calligraphy, geometric ornament, vegetal arabesques, and abstraction are unifying elements, there is also a great variety of styles and artistic expressions to be found across a vast geography.

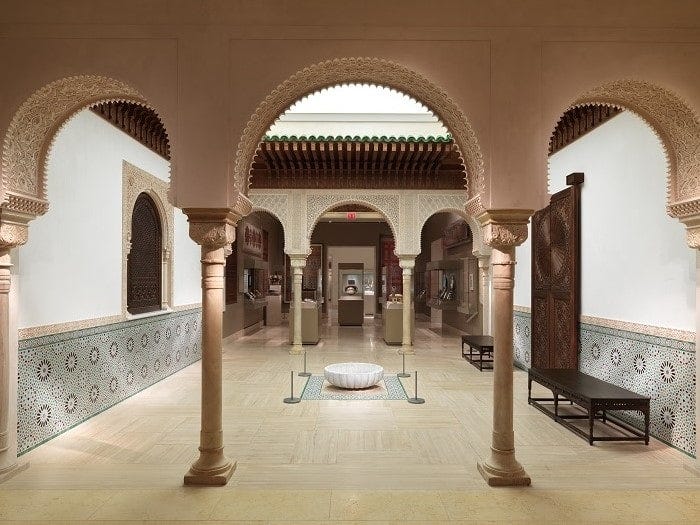

Spain, North Africa, and the Western Mediterranean (8th–19th centuries) (Gallery 457)

Ten years on, how would you say the renovation has facilitated more meaningful engagement with the Museum's collection of Islamic art and artifacts?

We have had over three million visitors to the permanent galleries and have done special exhibitions, books, and other projects. All of these resources have provided an appreciation for the arts of the Islamic world for local and global audiences. Visitors have been able to see outstanding works of art and understand the context and history in which they were produced.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Patti Cadby Birch Court: Moroccan Court (Gallery 456)

What do you hope visitors will glean from the redesigned space?

For our 10th anniversary, we are making a few modifications to the galleries. These will include works from underrepresented traditions of Islamic art as well as some contemporary works. We hope that visitors will expand their understanding and appreciation of the art in new ways.

In celebration of the 10th anniversary, the Heirloom Project will present jewelry, ceramics, textiles, and more by artisans who pursue historic techniques and design traditions. What makes craftsmanship in this vast and varied region so exceptional?

Many of the regions represented have preserved traditions of crafts and creativity, such as block printing, embroidery, ceramic production, glass blowing, and stone carving. The aesthetics are beautiful and the techniques extraordinary.

The Blooming Poppies collection, designed by Madeline Weinrib in partnership with Good Earth

Can you tell us a little bit about the floorspread fragment that inspired our Blooming Poppies collection? What's the significance of the poppy motif?

The poppy motif is one of the most famous among a repertoire of beautiful floral motifs in Mughal art—a single plant shown in profile with three blossoms and small buds growing from it. This motif is repeated all over the textile, which was possibly a floor covering or wall hanging. Its irregular shape indicates that it was adapted to a particular function. The flowers are large and bold but their leaves and petals are delicately articulated. They were likely created with stencils or blocks and also painted by hand and dyed. The color remains vivid thanks to the famous kalamkari dying technique.

Poppies were admired for their form and color, and were also the source of opium, which was used at the royal courts by the ruler and the nobility.

Fragment of a Floorspread, late 17th century. Islamic, Mughal period (1526–1858). Cotton; plain weave, mordant-painted and dyed, resist-dyed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Alice and Nasli Heeramaneck Collection, Gift of Alice Heeramaneck, 1982 1982.239a

Do you have a favorite object in the collection?

My favorites keep changing. Right now I am very taken with a beautiful dark green jade inkwell, which was made for the Mughal emperor Jahangir by a craftsman named Mu'min in 1618–19. Nephrite jade is very hard to carve, but he has created a beautiful, balanced shape, Persianate in style.

Inkpot of the Emperor Jahangir, dated A.H. 1028/A.D. 1618–19. Mu'min Jahangir (Indian). Nephrite, gold. The Sylmaris Collection, Gift of George Coe Graves, 1929 29.145.2