He is a figure indelibly associated with the sophistication of his cosmopolitan hometown, Vienna—who during his life kept to the same routine every day, rarely socializing with fellow cultural luminaries. He is an artist associated with sensuous, even erotic, depictions of women—who never married. His intriguing paintings of society figures, sex workers, and other subjects offer rich psychological depth—yet he never looked in the mirror to paint his own likeness.

Perhaps it is such contradictions—in addition to the sheer beauty of his paintings—that make Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) one of the art history's most enduringly popular artists.

Serena Pulitzer Lederer (detail). Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918). Oil on canvas, 75 1/8 x 33 5/8 in., 1899. Purchase, Wolfe Fund, and Rogers and Munsey Funds, Gift of Henry Walters, and Bequests of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe and Collis P. Huntington, by exchange, 1980

Trained at Vienna's School of Applied Arts, Klimt launched his career with the Künstler-Compagnie (Artists’ Company), founded with his brother Ernst and fellow painter Franz Matsch. The trio's traditional, decorative approach to large-scale projects earned them mural commissions from bourgeois clients throughout Austria and Europe.

Following the premature death of Ernst in 1891, Gustav Klimt and Matsch won a commission to create ceiling artworks for the Great Hall at the University of Vienna. First announced in 1894, this problematic project marked the end of a successful partnership—and announced the arrival of Klimt's groundbreaking new style. (When Klimt's two preparatory drawings for his part of the Great Hall commission were finally displayed, in 1900 and 1901, they attracted tens of thousands of visitors—and vociferous protests.)

Reclining Nude with Drapery, Back View. Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918). Graphite, 14 5/8 × 22 3/8 in., 1917–1918. Bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982

In response to the currents of modernism washing across Europe—and in reaction to the ultra-conservative tastes of Viennese patrons—Klimt quit the establishment Künstlerhausgenossenschaft (Vienna Artists’ Association), and, along with 20 fellow artists, founded the Vienna Secession in 1897. In a distinctive exhibition hall whose peculiar facade, gold filigree dome, and sinuous Art Nouveau friezes indicated a new point of view, this iconoclastic society produced frequent exhibitions that both scandalized and thrilled cultural sophisticates. Klimt's famous Beethoven Frieze was created for 14th Secession show, in 1902—and remains installed in the building today.

Textile samples (details). Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918); manufactured by Wiener Werkstätte. Silk, ca. 1920. Gift of Joanne F. du Pont and John F. Pleasants, in memory of Enos Rogers Pleasants, III, 1984.

As the 20th century arrived, Klimt continued to develop his singular vision. The mysticism of the Symbolist movement made an impression on the artist, and he was deeply influenced by the medieval mosaics he saw on travels to Venice and Ravenna in 1903. Some of his best-known works—including the dazzling Kiss (1907–08) and his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer— (1907) followed. Klimt was an associate of the famous Wiener Werkstätte, whose members sought to infuse high design principles into the applied arts; the collective produced the famous Tree of Life friezes he designed for the Palais Stoclet in Brussels, as well as textile patterns after his motifs.

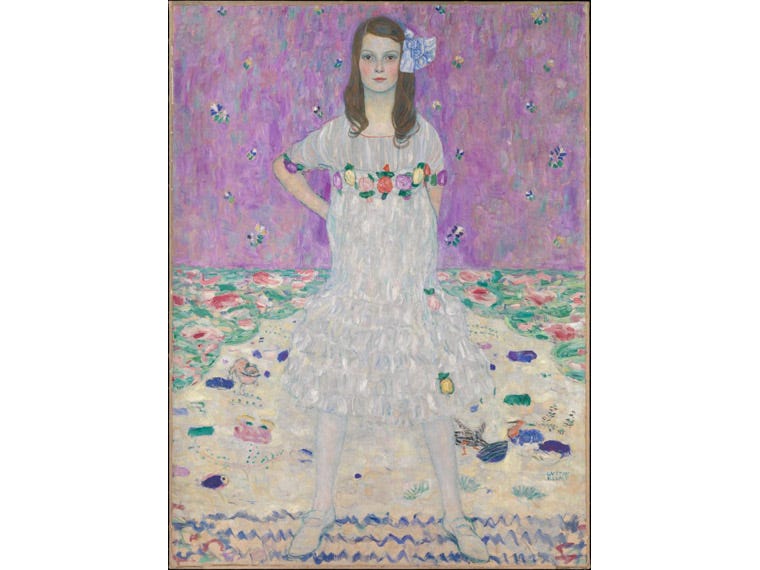

Mäda Primavesi. Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862–1918). Oil on canvas, 59 x 43 1/2 in., 1912–13. Gift of André and Clara Mertens, in memory of her mother, Jenny Pulitzer Steiner, 1964

During the last decade of his life, Klimt turned almost exclusively to depicting landscapes and portraits—in particular, portraits of women. Perhaps it is in these paintings—where vibrant colors and shimmering surfaces paradoxically portray their subjects' inner complexity—that Klimt's artistic vision is most fully apparent. As the artist said himself, "Whoever wants to know something about me—as an artist, the only notable thing—ought to look carefully at my pictures and try to see in them what I am and what I want to do."

The Met Store offers fun and beautiful products inspired by the work of this singular artist. Discover our own takes on Klimt today.

Clockwise from top left: Gustav Klimt Action Figure, $28; Klimt Domed Magnets, $22; Klimt: Tree of Life Holiday Cards, $18; Klimt Mäda Primavesi Tote, $35